The frustration of hoping & not getting

Like any brand, politics is something we spend towards in exchange for something else. Unlike an ordinary purchase, we're uncertain what we'll get in exchange, which causes frustration. I explain why.

The Politics Gap

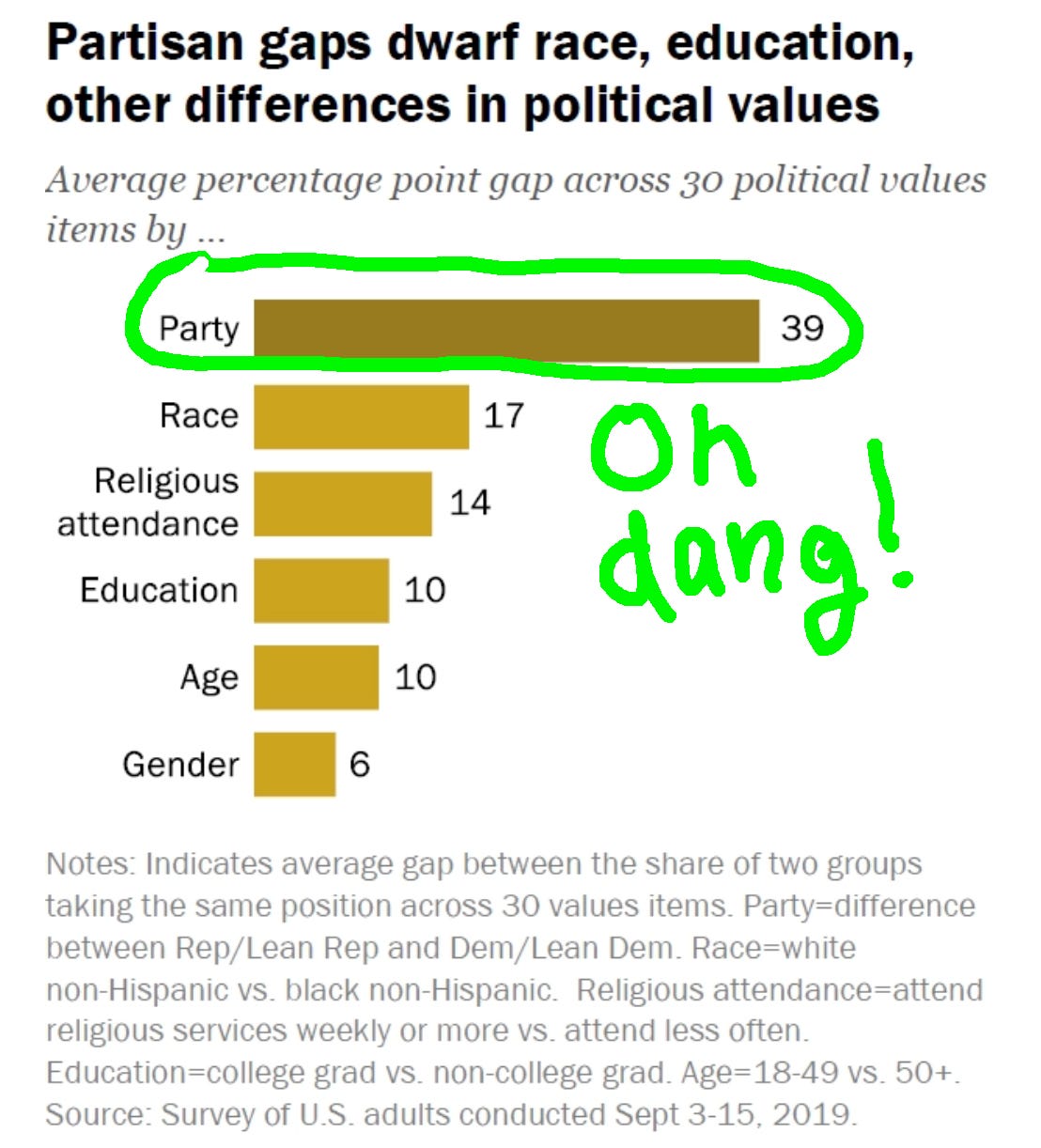

Politics is no different than any other brand: we spend something in exchange for something. Politics drives our thinking and forms a large part of our identity. This is supported by the fact that rather than race or religion, people’s attitudes on issues diverge the most on the basis of political party:

Across 30 political values – encompassing attitudes about guns, race, immigration, foreign policy and other realms – the average partisan gap is 39 percentage points. - ‘In a Politically Polarized Era, Sharp Divides in Both Partisan Coalitions’

🙏🙏🙏 New here? I HOPE (get it?) you’ll subscribe:

In an ordinary brand exchange, outcomes are certain: spend money, receive product or service. Political brand exchanges are different in that they come with high costs and uncertain results. I’ll explain how this frustration is unique compared to typical brand engagements.

Show us the money, and some other stuff

When we make a purchase, money isn’t the only asset exchanged—we also exchange time and hope. The total value the buyer hands over in a purchase is equal to some combination of the three. The value of each asset relative to the other depends on what’s being purchased and the consumer’s supply of each.

From the consumer’s perspective:

Money: The medium of exchange that facilitates settlement of the purchase.

Time: An asset spent pre and post purchase. Typically spent deciding on the product (pre) and using the product (post).

Hope: Exchanged by the consumer to reach a desire or desired outcome. Hope is exchanged for a marginal increase in meeting these desires.

Generally, someone buying their 5th car exchanges far less hope than the person who is buying their only car with the hope it reliably gets them to work everyday.

The difference a brand makes

For many products, branding is the lever that increases the amount of hope a buyer is willing to exchange. After all, association with a brand is a value that’s distinct from a product’s intrinsic value. Brand Value. Think Yeezy sneakers versus Target sneakers.

Brand value accounts for major differences in prices across similar items. It’s why a men’s winter coat can cost $40 at Costco, and cost $999 elsewhere. Both coats’ intrinsic values and compositions are similar—to keep warm and dry—but each brand comes with different value.

Let’s put all of this into context with my recent tennis racquet purchase:

Money: I hand over $175 for the racquet. Everyone agrees I own it now.

Time:

Pre-sale: I spent about 4 hours researching what’s best for me—racquet models, and stringing techniques and types.

Post-sale: I spend time using the racquet, acclimating to its nuances, re-evaluating my decision to buy it, and constantly assessing my enjoyment of it.

Hope: I desire to be a better tennis player and I hope the purchase of the racquet will get me closer to that. I see that Rafael Nadal, who’s very good at tennis, uses a similar racquet and I desire to do anything on the court like him, even just sweat like him.

It’s safe to say I have more money and time than I do hope of reaching Rafa-level proficiency. So in this purchase, I weight money and time more heavily.

Why politics can suck

If I exchange money, time, and hope, I know I’ll get the racquet. Politics is not the same.

Like the racquet, money, time, and hope are exchanged for brand value. The brand value in politics is the association with the policies and personalities of a chosen party. But unlike the racquet, you may not get the intrinsic value of the product—a desired political outcome.

This means that there is no fixed cost in politics that is certain to provide a desired outcome. Because of that, the marginal amount of desire received in exchange for hope is unpredictable. A party may win in a landslide or get trounced, it can be tough to know.

Even if we don’t want to, we spend time hearing about politics, talking about it, and reflexively calibrating our lives around it. Most people do not spend a cent directly on politics. Politics, in contrast to most products, requires a larger exchange of hope and time relative to money.

And, unlike an ordinary brand exchange, the value we assign hope relative to time and money is substantially higher. Whether it’s medicare for all or a wall, we want big things to happen in politics.

Finally, we’re conditioned to expect that when we give more, we get more. If footlongs are $5, $10 will get me two. Putting more time and hope into politics wrongly leads us to believe we’ll get more of our desired outcome.

In summary:

Political outcomes are unknown.

In politics, the amount we spend and value we place on hope and time are higher relative to traditional products.

We don’t always get more if we give more.

The constant in all of this is a lack of control. Despite all of this, politics is the brand to which we assign the most hope and the most time.

Therefore, frustration from politics arises because politics’ ambient nature is a never-ending reminder of our lack of control of the world around us.

********

💰💵🤑 If you liked this, it’s worth it to forward this to a friend, or share:

⏰⏱🕰 I won’t waste your time, promise. Subscribe.